Fossils are found along the entire Tour de France Femmes route but today we find a lot along the Lot. We also meet a pioneer in this field: the British paleontologist Mary Anning.

The starting point of this stage lies at 125 meters about sea level in Cahors. It’s nestled in a winding meander of the river Lot. Cahors is known for its UNESCO World Heritage listed medieval fortified Valentré Bridge. There are numerous notable geological sites along the Lot River between Cahors and Rodez. While the riders need to keep their eyes on the road, spectators can enjoy the scenery through the geological lens.

From the lowlands of the Aquitaine Basin and on the winding trail along the meandering river, the route leads through some spectacular geological sites cut into stone. One of these geological sites is the towpath in Bouziès carved into the craggy cliffs. It bears stories of the distant past when life on Earth was pendulating between struggling and thriving.

The time of dinosaurs

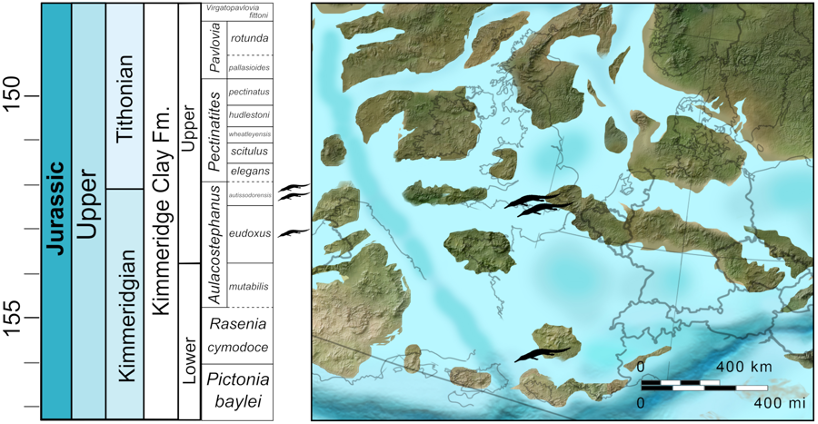

The cliffs on Bouziès are made of pale limestones. They were deposited in a marine basin that was once present when dinosaurs and plesiosaurs roamed the lands and seas in Jurassic time. The configuration of lands and seas looked very different back then. During the Jurassic period the supercontinent Pangaea began to break apart into smaller landmasses. This included Laurasia which would eventually become North America, Europe, and Asia and Gondwana which would eventually become South America, Africa, Antarctica, India, and Australia.

The Jurassic period was a time of major evolutionary developments including the diversification of angiosperms (flowering plants) and the emergence of the first mammals. The first birds also appeared during the Jurassic period, including Archaeopteryx. That is a transitional species between dinosaurs and modern birds. Many of these mysterious animals that we know of through the fossil record fell victim to a major extinction event at the boundary of the Triassic-Jurassic. And as so often in the geologic past, life reinvented itself and started thriving again. Until the next mass extinction event happened at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary (also see TDF stage 3).

Mass extinction leads to fossils

A mass extinction is an event in which a significant proportion of Earth’s biodiversity, across multiple taxonomic groups, is lost in a relatively short geological time frame.

Such an event is generally considered to involve the loss of at least 75% of species within a particular ecosystem or on a global scale. Mass extinctions are often associated with catastrophic environmental changes such as rapid climate change, asteroid impacts, volcanic activity, or other factors that can alter the Earth’s ecosystems and disrupt the balance of life on the planet.

All mass extinctions in Earth’s history involved major perturbations to the carbon cycle, the carbon content of the atmosphere and rapid changes in the chemistry of the ocean. The most famous mass extinction event in Earth’s history is the one that occurred at the end of the Cretaceous period. That resulted in the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs and many other species.

Fossil hunt around the Lot

During Cretaceous times, the once connected landmasses of Africa and South America broke apart to form the Atlantic Ocean. The region along the Lot River experienced those tectonic forces. This caused intense karstic activity which formed phosphorite in caves that gave rise to the perfect conditions for a fossil “Lagerstätte”. As a result, thousands of fossils are preserved exceptionally well in these rocks.

These rocks and fossils recorded the climatic and environmental conditions for the evolution of life. They are the European reference section for the upper Eocene and Oligocene epochs. For this reason, the Causses de Quercy is a Geopark today.

Pioneer: Mary Anning

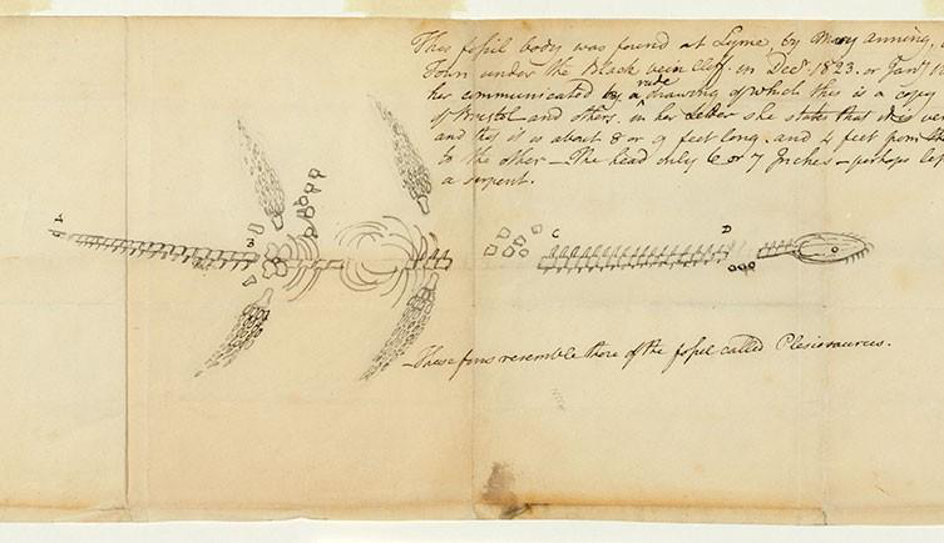

After a dive into deep time and the humbling fact that life had to reinvent itself several times in the aftermath of cataclysms, we may look differently at the Jurassic landscape and its past life locked into stone. Maybe it’s no surprise that 19th century palaeontologist Mary Anning comes to mind.

She was born in a coastal town of England, which is now called the Jurassic coast. From a young age, she collected fossils to supplement her family’s income. Anning’s talent for finding, documenting and identifying fossils was remarkable. Her most significant discoveries included the first complete skeletons of an Ichthyosaurus, a Plesiosaurus and a Pterodactylus.

While her work in the field of palaeontology contributed greatly to our understanding of prehistoric life, and the establishment of the geologic time scale, her achievements were not fully recognized during her lifetime. She faced significant obstacles as a woman in a male-dominated field along with lifelong financial hardship.

Today, Mary Anning is celebrated for her ground-breaking work in the field of palaeontology. Anning’s legacy continues to inspire future generations of scientists. It lives on in the now UNESCO world heritage site of the rugged Jurassic Coast and is immortalized in the tongue twister “she sells sea shells by the seashore“.