The white jersey for the best young rider is always a great indication of future greatness. The likes of Tadej Pogacar or Egan Bernal even won the Tour de France in the white jersey. Today we will investigate a mineral for all things white and some battery power for the wireless shifting systems.

Stage 11 takes the peloton from the mountainous Massif Central to the plains of the Bourbonnais. Although this stage is likely to be decided in a sprint, a few enthusiastic climbers might decide to join the breakaway and test their legs on the two small hills in the first third of the race. It is at the top of the second climb that the riders will pass the geologic highlight of the day: the quarry of Beauvoir.

This quarry is well visible from above. Its white colour is striking amidst the green forests that surround it. The white colour comes from the mineral kaolinite that has been mined here since 1852. Kaolinite is a clay mineral that is abundantly used to manufacture all things white such as paper, ceramics, and paint. Although the white jersey is most likely not produced with this dye.

About 70% of the global kaolinite production used to go to the production of the coating that gives paper its white color. By 2016 this figure dropped to 36%, partly due to the increasing popularity of digital media. The market value of all the kaolinite mined in 2021 amounts to 4.24 billion USD, an amount comparable to the yearly GDP of Sierra Leone.

The history of white

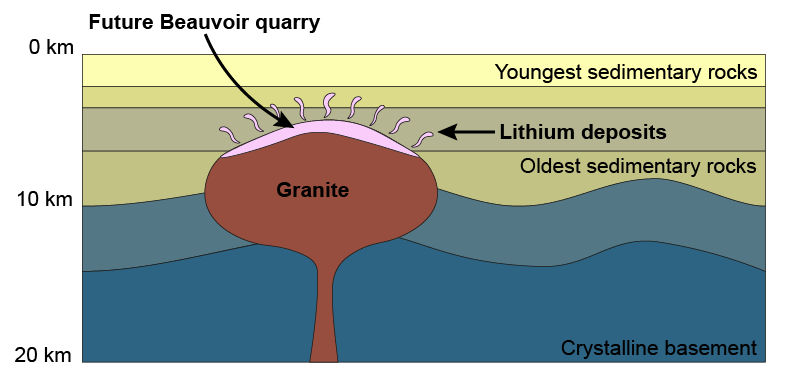

How did all that kaolinite get here? Well first, we need a lot of a group of minerals called feldspars. These minerals can be recognised by their square shapes and milky white to pink colour. These minerals can be found in many crystalline rocks. In the Massif Central most feldspars are found in a rock called granite.

This is a rock that forms when lava, or liquid rock, slowly cools down and solidifies in a magma chamber deep under the surface. These lavas formed during the so-called Variscan orogeny, a mountain building event that culminated when what is now western Europe collided with North America, about 300 million years ago! Over the course of these years the rocks overlying the now-solid magma chamber were slowly eroded away. The result was the exposure of the granites to the elements. As the feldspars came into contact with rainwater, which is slightly acidic, they were transformed into clays such as kaolinite.

More power!

To society, these granites are not just interesting because they are broken down into future paper coatings. The magmas from which granites are made contain many precious metals. The most well-known of which is lithium. The crystal structure of the minerals in granite does not have space for these metals. So as the granite crystallizes out of the magma, these metals prefer to stay in the remaining liquid rock. That is of course until the last bit of lava solidifies and the metals have nowhere else to go! The top of the magma chamber, which happens to lie directly under the Beauvoir quarry, is thus chock full of the stuff that we now use to make batteries for nearly everything: even the electric group sets used by the peloton have Lithium batteries in them.

Drive on!

The French geological service predicts that there is enough lithium below the Beauvoir quarry to provide batteries for 700,000 electric cars. However, there are almost 40 million cars in France alone. We will need a lot of other places like the Beauvoir quarry to reduce our carbon footprint.

Unfortunately, mining Lithium, or any of the other precious metals found here, is not very good for the environment. It requires large amounts of water, another resource that is becoming increasingly scarce. Extracting metals from the rocks pollutes this water to such an extent that it becomes toxic for most organisms. It is also not a renewable resource. The earliest estimate for the next collision between North America and Europe is about 200 million years from now. However, many geologists question if it will ever happen again. New magma chambers are just not going to pop up in time to be mined for batteries.

If, and to what extent the Beauvoir quarry, and similar geological locations in the Massif Central, should be exploited will likely be fiercely debated in the coming years. Perhaps the climbers in the breakaway realise they should seize this opportunity to push on, as this hill could disappear in the coming years…