The unremarkable, gentle profile of today’s stage clearly favors the sprinters. However, the shallow hills hosting vines and grazing cows are nothing but a superficial veil draped on some enormous mounts that no cyclist would ever consider to climb.

Hiding not far below the tarmac are gigantic columns of salt, so called salt diapirs, rising from over 2000m depth. One such diapir is in fact the sole reason of existence for the biggest spa town of France and today’s starting location, Dax. More on that later, let’s first dive into the origin of salt diapirs.

250 million years of sediments

Today’s stage sends the riders over the Aquitaine Basin. This is a gigantic geologic basin of Paleozoic basement rock, measuring about 65’000 km2. During the past 250 million years it has gradually filled up with sediments. Think of alternating layers of sand, silt, carbonates and, yes, one mighty, peculiar layer of salty clay. This evaporite, as it is called in geologic terms, was deposited during the Late Triassic (around 210 million years ago). It was a period of tectonic extension and analog formation of new sub-basins.

It was a hot climatic period, warmer than our current climate. The surface waters that were flowing into the newly formed basins evaporated rather quickly. What remained was the salty clay that the rivers had picked up along their way. This process went on for millions of years, resulting in a layer of evaporites of multiple hundreds of meters thick!

Invisible salt mountains and sprinters

Alright, but how did this horizontally deposited salt get molded into mountains? Picture today’s peloton of pro-cyclists, approaching the finish in Nogaro. With 400 meters to go, the top sprinters are still hiding behind their lead-out men. Then, as soon as they pass the 200-meter mark, the pressure is on. The fastest and nimblest of the bunch will squeeze forwards into the tiniest gaps.

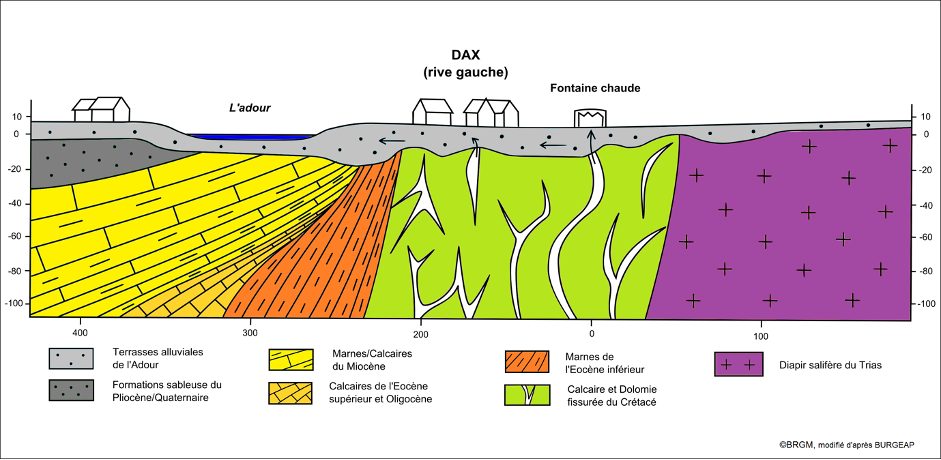

The evaporites were our top sprinters: pressurized by the younger, yet heavy overlying layers of carbonates and sand. The more ductile salty clay squeezed up into the cracks that formed during another phase of extension in the Early Cretaceous (around 120 million years ago). A fair bit later, the now existing salt ridges suffered a crush from the south when Iberia collided with Eurasia. That was the event that uplifted the Pyrenees (60 to 20 million years ago). Et voila, there you have it; steep, distorted, invisible rises of salty clay, just under our pedals.

Let’s take a bath!

Great, bring in the spa aspect! Well, about 75 km south of Dax, Pyrenean precipitation seeps into fissured Cretaceous limestone. This water flows north, underground, downstream through the folded limestone to a depth of about 2 km, until it hits our ‘Diapir de Dax’. Remember how the salt had powerfully squeezed its way up? Its brute force caused the overlying limestone hosting the water to bend upwards.

This is why today, after a trip of 20,000 years, water that precipitates in the Pyrenees can flow up along the flanks of the diapir. There it heats up (salt is an excellent conductor of geothermal heat) and gets charged with salty minerals. Eventually, this water springs in multiple locations over the region. The most famous one is the Fontaine Chaude, the heart of Dax since pre-Roman times. With a yearly flux of over 2’000’000 liters and a temperature of 64 degrees Celsius, this spring truly deserves its name.

Now, let’s find out which riders are worth their weight in salt.