Cycles, cycles. They go around and around, like the geology of Paris-Roubaix. This story is about producing, circulating and recirculating of dust. In Paris-Roubaix every year, and on the hills of Northern France every era. The dust, or mud and dirt when wet, comes from one single geological source: loess. Surely, the riders will have cobbles on their mind. Man laid hard stone, quarried from the edges of the nearby Ardennes, solidified from the depth of the earth 435 million years ago. They were imported by French farmers and road workers since the 1800s. But we won’t talk about the cobbles.

We talk about the dust on their bikes, tyres, legs and faces. Dust is always there whether the race is wet and slippery or dry and dusty. This story is about dust and its connection to ice-age cycles, wind, water and weathering, French-Belgian hills and valleys and lost plains now below Channel and North Sea. The dust of Roubaix tells the story of the geology of Paris-Roubaix.

Old dirt

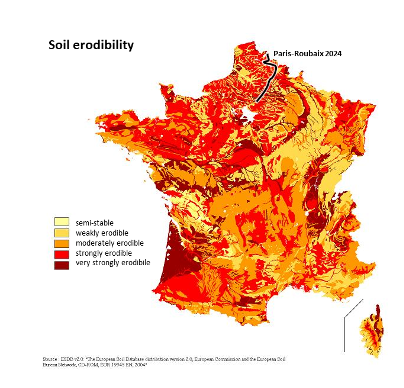

The Roubaix dust originates from weathering of bedrock, simple as that. The dust is composed of fine grained slivers from North French sedimentary source rocks just 50-100 million years old. That is much younger than hard stone from the Ardennes. The natural break down of the bedrock and with that the production of silt (the geological name of our magic Roubaix dust) went up a gear up in the last million years. It was then when intensive ice-age climate cycles hit the area. It caused the region to experience alternating rounds of ice-age freezing and warm-interval forestation.

Silt is produced all the time, regardless of the climate condition. In cold phases because water freezes up in cracks breaking substrate down physically. In warm interruptions because roots grow into cracks and release saps that attack the substrate chemically to release nutrients. The particles that break away are fairly small, mostly that of the size between that of sand and clay. Silt are powdery grains measuring smaller than 50 micrometer (0.050-0.004 millimeter). Silt is easily erodible, and easily transportable both by water and by wind. It also ends up in all parts of the bike, and in the ears, hairs, eyes, between your teeth etc. Loess is the name we give to these silty wind deposits (read more). Many of the soils that produce the dust along the Paris-Roubaix course turn out to be loess soils.

The dirt breakaway

Where silt was produced during phases with forest cover, it is held in place by tree-roots. It’s like holding an eager peloton in the neutral zone of the race. When Celts, Belgae and Franks cleared the forests to become fields for agriculture, now millennia ago, the dust was allowed to escape. We have a breakaway! It embarked on an ambitious journey away from the bunch.

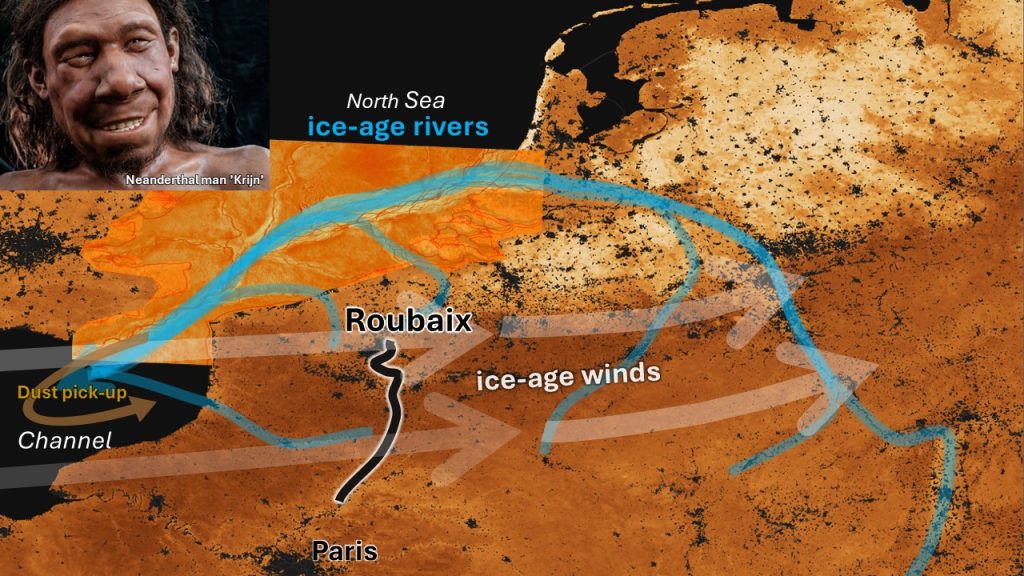

Just as well, when ice-ages commence and vegetation deteriorates or dies, the dust tends to break free as well. Escaping dust washes down by annual snowmelt during summers in ice ages, and by rain, along roadsides into gullies in our modern time as well. Today it reaches rivers and seas of the North Sea. Roubaix drains to that via Lys and Scheldt and the English Channel (areas closer to Paris drain to that, via Somme). That is when it’s not trapped and clogging up places half way. In the ice ages it reached these same areas, perhaps more efficiently – but the North Sea and Channel were river plains then, as global sea-levels stood much lower. They just arrived at their destination faster.

Dust in the wind

Some Neanderthals tracking herds of Mammoths passing in late summer, pinching their eyes against the dust that strong winds had swept up from the river plains. That was easy for them with their big eyebrows, riders nowadays need glasses for that. Pesky geology in Paris-Roubaix!

Winds are blowing mainly from the west. Dust taken from barren parts of the river bed that had fallen dry, exposing fresh silty sediment that had arrived there during spring snowmelt floods the season before. That cycle of dust being picked up took all winter when our team of Neanderthals had retreated to shelters along the Somme valley.

Dust that ice age winds would bring back to Roubaix’s hilly source regions. Recycling the dirt, blanketing the terrain. A giant gyre over Northern France, a tandem of transport agents, a downvalley étape towards the plains, and a downwind étape back into source hills. Good for agriculture and erosion millennia later. Challenging for riders one day each year.

Cycling dirt

So, to summarize: it is due to the cyclical movement in the ice ages that there is so much mud or dust along the roads of this great race. Geographically, Roubaix can be seen as the nave of all this cycling, the eye in the storm. Not a sand storm but a silt storm, at least for the leg of the cycle going west to east from the Channel to the hills. And the other leg, from hills to plains in what now is the sea? That was a watery one: the away leg by rivers, the return leg by wind. Wonder what Strava makes of that?

As such Roubaix is the perfect place to finish, shower off, and prepare for another round… next year, next cycle. The landscape of Northern France wears a coat of loess, just as the riders do after passing it, laid down by the windy leg.

Although farmers liked this soil for its fertility and fairly easy ploughing and cultivation, they didn’t like it when transporting the harvest away from the fields. That’s why crude cobbles were imported to pave dirt roads.

It’s all about the dirt, man!

But it’s not the cobbles that count but the dirty men and women, that make the race!

Don’t let any cowboy-headed geologist fool you with attention to mining spoil, cobble quarry or calcareous rock subcrop defining young Cenozoic cuesta hill features around the Paris Basin, or shoved up old Paleozoic porphyric blocks. Oh, no! Be undercooled and instead please focus on the brown to grey soil, silt, dust, loess, mud, dirt – whatever you call it. Because that’s where the cycling is at. That’s the geology that makes the weathered faces. That’s the true geology of Paris-Roubaix.

Marjolein travelled to northern France and tells you why you actually need cobblestones. It’s the löss.