Eels? Well, actually we have eel-like creatures today but not on the menu of the riders after stage 6. In these eel-like animals called conodonts we get to know another guide fossil like we did on stages three and seven of the men’s race well. But there is more on stage 6 because we are on a very important geological boundary.

A cyclist crossing the region of Tarn today sees only the benign surface of a rolling landscape and lush farmland. Nothing betrays the history of tectonic upheavals hidden beneath the surface. Nothing? If you lift your eyes from the road and look to the horizon on your left, towards the south, you see the ominous outline of the Lacaune Mountains. Towering behind them is the Montagne Noire. The mountains seem like a different planet from the green countryside you pass in the Tarn river valley. Its thin, arid, acidic soils on the slopes of rocky cliffs host only the most defiant pine trees.

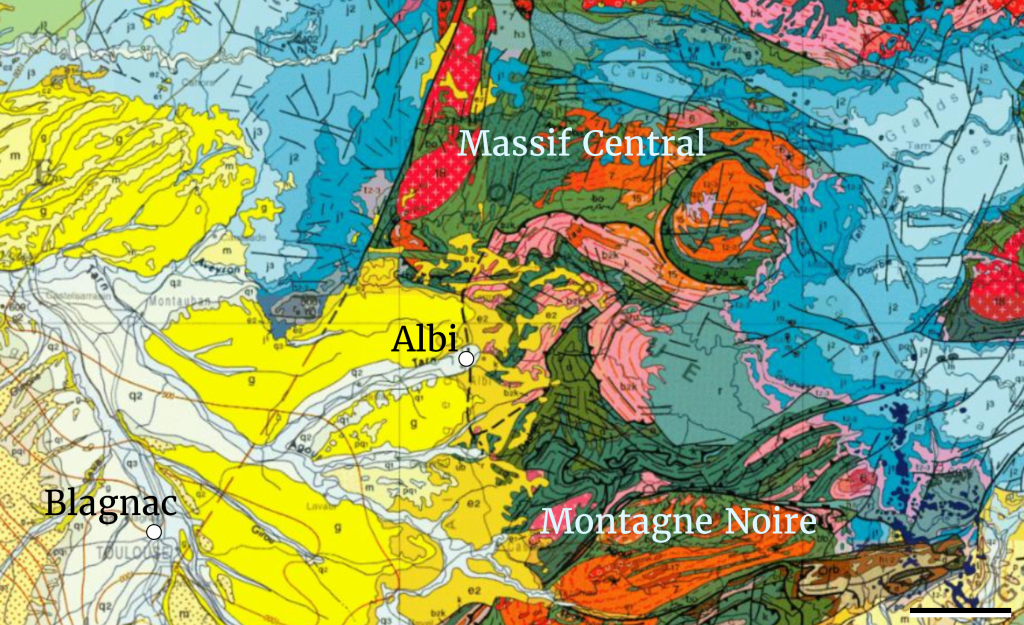

As you ride from Albi to Blagnac you travel along one of the most important boundaries between geological units that form France: Massif Central to your right and Montagne Noire to your left. They are witnesses of a mountain building episode that took place over 300 million years ago, in the Devonian and Carboniferous periods.

Despite their much older age, they tower over the soft bedrock of the Tarn river valley, because they were solidified into hard crystalline rocks from swaths of lava produced by volcanoes once active here. Underneath your wheels, covered by unassuming clays and sands, an isthmus of crystalline rock connects Massif Central to Montagne Noire.

Too hot to handle

The mountain building and intense volcanism during the Devonian means not only bad news for modern farmers looking for fertile soils. It is also a challenge for geologists seeking to piece together the history of the planet.

Mountain building is akin to a giant meat grinder: rocks get jumbled up, sank to great depths, molten and spewed out in unexpected places. All these environmental upheavals surely had affected the life on Earth at the time, but good luck finding fossils in the meat grinder!

The more precious are the few places where they are preserved. And Montagne Noire hosts two Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points. They are geological localities which are a global reference for dividing the Earth’s history. In this case we are looking for the bases of the Frasnian and Famennian stages. They both form the Upper Devonian which corresponds to the time of the massive volcanism which contributed to one of the “big five” mass extinctions. Also see stage 4.

A pioneer and old eel-like eels

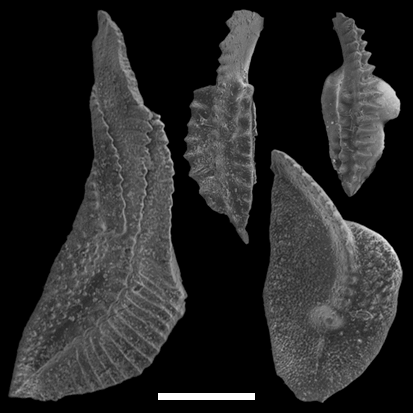

Global stratotypes are often based on an evolutionary change in an organism that we can find everywhere across the world. But how to find such an organism at the time of a mass extinction when everything dies out? The deep end, so the oldest eras, of the geological timescale relies hugely on conodonts. They are extinct small eel-like animals which left behind thousands of minuscule teeth.

The teeth of these ancient eel-like creatures evolved and diversified rapidly, allowing us to track evolutionary changes in the depths of the Palaeozoic Era. This way we achieve a high resolution in the geological timescale. They are guide fossils like we saw on stage 3 too.

The rich history of co-evolution between conodonts and their environment, including the record of rapid warming and the following collapse of trophic networks in the unique localities at Montagne Noire we owe to Dr. Catherine Girard.

Catherine, still active at the University of Montpellier, pioneered the use of modern ecological and geochemical analyses in conodonts in this area. She helped bringing the paleontological heritage of France to international attention and thus revealing the mechanisms of evolution at the sharp end of environmental changes.

Conodonts at Montagne Noire record an unprecedented warming which boiled a large part of the biosphere. It’s not unlike the challenges faced by the riders today as the global climate becomes more unpredictable.